-

Downing Street suggests UK should be seen as model of racial equality

Anger as long-awaited report on race and ethnic disparities concludes ‘claims of institutional racism not borne out’

Downing Street’s official response to the racial justice movements connected to Black Lives Matter has suggested the UK should be seen as an international exemplar of racial equality, and has played down the impact of structural factors in ethnic disparities.

The much-delayed report by No 10’s Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities is likely to spark an angry response from activist groups, with race equality experts describing it as “extremely disturbing” and offensive to black and minority ethnic key workers who have died in disproportionate numbers during the pandemic.

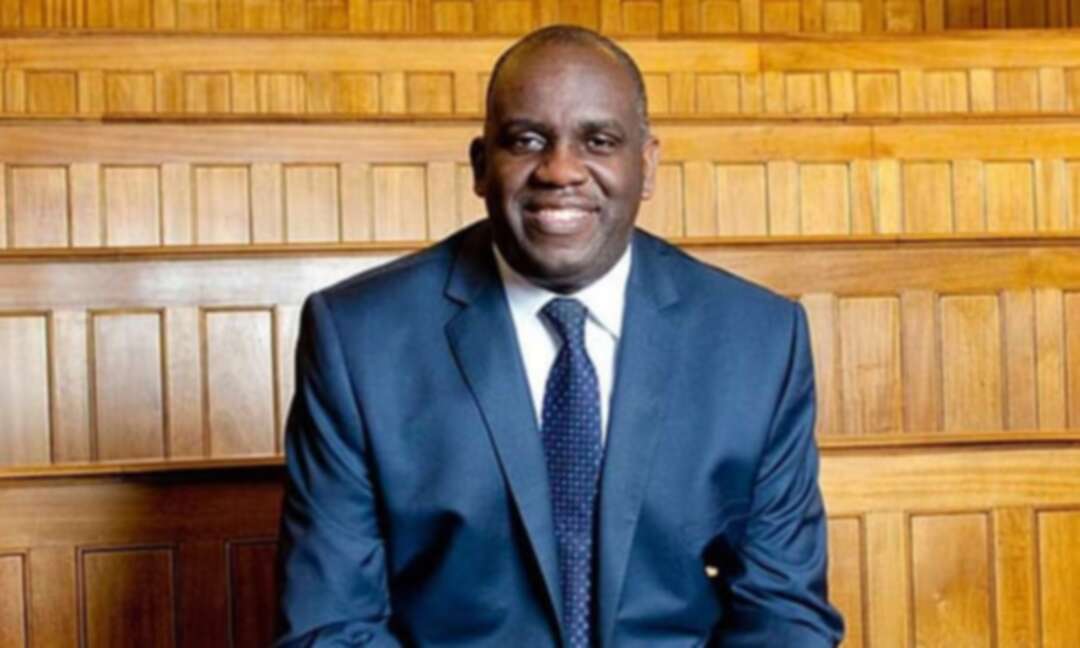

The commission’s chairman, Dr Tony Sewell, said the report did not deny that racism exists in Britain, but there was no evidence “of actual institutional racism”.

He told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme on Wednesday: “What we have seen is that the term ‘institutional racism’ is sometimes wrongly applied and it’s been a sort of a catch-all phrase for micro-aggressions or acts of racial abuse. Also people use it interchangeably – systematic racism, structural racism

A preview summarising the report, which is described as a “major shift in the race debate”, notes that while overt racism does still exist in the UK, achievements elsewhere should make the country “a model for other white-majority countries”.

It emphasises the academic achievements of children from minority ethnic backgrounds, saying that many students from these communities do as well or better than their white peers. It does, however, call for extended school days to help disadvantaged pupils catch up.

The 264-page report has 24 recommendations. However, these are not yet known, as the Government Equalities Office, which is organising its release, opted to put out only a brief summary of the findings on Tuesday.

One of the main conclusions of the report appears to be a pushback against the idea of structural racism. In an open rebuff to the arguments of the BLM movement, and the protests that erupted after the death of George Floyd in the US, the report is described as saying “the well-meaning idealism of many young people who claim the country is still institutionally racist is not borne out by the evidence”.

A spokesperson for Black Lives Matter UK said that while the report focused on education, “it fails to explore disproportionality in school exclusion, eurocentrism and censorship in the curriculum, or the ongoing attainment gap in higher education.

“We are also disappointed to learn that the report overlooks disproportionality in the criminal justice system – particularly as police racism served as the catalyst for last summer’s protests. Black people in England and Wales are nine times more likely to be imprisoned than their white peers, and yet, four years on, the recommendations from the Lammy review are yet to be implemented.”

Halima Begum, the chief executive of the Runnymede Trust, said: “As we saw in the early days of the pandemic, 60% of the first NHS doctors and nurses to die were from our BAME communities. For Boris Johnson to look the grieving families of those brave dead in the eye and say there is no evidence of institutional racism in the UK is nothing short of a gross offence.

“The facts about institutional racism do not lie, and we note with some surprise that, no matter how much spin the commission puts on its findings, it does in fact concede that we do not live in a post-racist society.”

The report does note that some communities are still very affected by historical cases of racism, creating “deep mistrust” in the system, adding: “Both the reality and the perception of unfairness matter.”

One conclusion is that the term BAME, (black, Asian and minority ethnic) is “of limited value” and should no longer be used by official bodies. As expected, it also calls for a move away from unconscious bias training.

On pay and other work-based disparities, the report calls this “an improving picture”, saying that overall, “issues around race and racism were becoming less important and, in some cases, were not a significant factor in explaining disparities”, with areas such as social class viewed as of equal importance.

The report says: “We found that most of the disparities we examined, which some attribute to racial discrimination, often do not have their origins in racism.”

The language contained in the precis appears to mirror much of the thinking of Munira Mirza, the head of the Downing Street policy unit, who is seen as a particular influence on Boris Johnson on race and other cultural issues. Mirza, who oversaw the appointment of the commission panel, is a longtime and outspoken critic of previous government attempts to tackle structural factors behind racial inequality.

The communities secretary, Robert Jenrick, told Sky News on Wednesday that the report suggested progress had been made, but the prime minister believed “there was more work to be done”.

The shadow foreign secretary, Lisa Nandy, told the same programme that disproportionate rates of school exclusion and arrest among black children underlined evidence of an institutional problem. It would roll back progress if the government sought “to downplay or deny the extent of the problem, rather than doing what it should be doing which is getting on the front foot and tackling it,” she said.

Maurice Mcleod, the chief executive of Race on the Agenda, described the conclusion of the inquiry as “government level gaslighting” and criticised the summary for claiming communities are being “haunted” by “historic cases” of racism, creating “deep mistrust” in the system that could prove a barrier to success.

He said the implications of the report were that “the reason so many black people don’t get on well in this society is because they are stuck in the past and this makes them mistrustful. So racism isn’t the problem, people talking about racism is the problem.”

He said: “We would argue that you cannot tackle structural racism if you don’t believe it exists. The only substantive thing in the report is the decree that the public sector should stop using the term BAME; 250,000 people didn’t march through our cities during a pandemic demanding better syntax.”

Black Lives Matter UK said the movement was “perplexed by the fact that the report claims to reject the term BAME, describing it as ‘of limited value’, yet uses the category to analyse income gaps. I’m doing so, the commission insidiously disguises the inequalities faced by Bangladeshi, Pakistani, Caribbean and African workers”.

In 2017, Mirza condemned an audit of racial inequalities in public services commissioned by Theresa May, writing that it showed how “anti-racism is becoming weaponised across the political spectrum”.

It is understood Mirza had initially hoped to involve Trevor Phillips, the former chair of the Equality and Human Rights Commission, who had referred to UK Muslims as being “a nation within a nation”, as a member of the new body. Her eventual choice to chair the commission, Tony Sewell, has also previously questioned the effects of institutional racism.

Begum said: “This commission long lost the confidence and the trust of the ethnic minority communities when it appointed Tony Sewell to lead it, a figure who asserts with others in this government that institutional racism does not exist.”

Sewell said, in a quote released with the report summary, that one finding was “just how stuck some groups from the white majority are. As a result, we came to the view that recommendations should, wherever possible, be designed to remove obstacles for everyone, rather than specific groups.”

He said: “Creating a successful multi-ethnic society is hard, and racial disparities exist wherever such a society is being forged. The commission believes that if these recommendations are implemented, it will give a further burst of momentum to the story of our country’s progress to a successful multi-ethnic and multicultural community – a beacon to the rest of Europe and the world.”

On the Today programme, Matthew Ryder QC, a former deputy mayor of London and a lawyer who represented the family of Stephen Lawrence, highlighted 2019 research from the University of Aberdeen which found that even when white working-class boys had lower educational qualifications and a lower likelihood of going to university, they had higher employment rates and higher social mobility than working-class people of ethnic minority backgrounds. “That doesn’t suggest racism has been removed from the system,” he said.

source: Peter Walker

Levant

You May Also Like

Popular Posts

Caricature

BENEFIT Sponsors BuildHer...

- April 23, 2025

BENEFIT, the Kingdom’s innovator and leading company in Fintech and electronic financial transactions service, has sponsored the BuildHer CityHack 2025 Hackathon, a two-day event spearheaded by the College of Engineering and Technology at the Royal University for Women (RUW).

Aimed at secondary school students, the event brought together a distinguished group of academic professionals and technology experts to mentor and inspire young participants.

More than 100 high school students from across the Kingdom of Bahrain took part in the hackathon, which featured an intensive programme of training workshops and hands-on sessions. These activities were tailored to enhance participants’ critical thinking, collaborative problem-solving, and team-building capabilities, while also encouraging the development of practical and sustainable solutions to contemporary challenges using modern technological tools.

BENEFIT’s Chief Executive Mr. Abdulwahed AlJanahi, commented: “Our support for this educational hackathon reflects our long-term strategic vision to nurture the talents of emerging national youth and empower the next generation of accomplished female leaders in technology. By fostering creativity and innovation, we aim to contribute meaningfully to Bahrain’s comprehensive development goals and align with the aspirations outlined in the Kingdom’s Vision 2030—an ambition in which BENEFIT plays a central role.”

Professor Riyadh Yousif Hamzah, President of the Royal University for Women, commented: “This initiative reflects our commitment to advancing women in STEM fields. We're cultivating a generation of creative, solution-driven female leaders who will drive national development. Our partnership with BENEFIT exemplifies the powerful synergy between academia and private sector in supporting educational innovation.”

Hanan Abdulla Hasan, Senior Manager, PR & Communication at BENEFIT, said: “We are honoured to collaborate with RUW in supporting this remarkable technology-focused event. It highlights our commitment to social responsibility, and our ongoing efforts to enhance the digital and innovation capabilities of young Bahraini women and foster their ability to harness technological tools in the service of a smarter, more sustainable future.”

For his part, Dr. Humam ElAgha, Acting Dean of the College of Engineering and Technology at the University, said: “BuildHer CityHack 2025 embodies our hands-on approach to education. By tackling real-world problems through creative thinking and sustainable solutions, we're preparing women to thrive in the knowledge economy – a cornerstone of the University's vision.”

opinion

Report

ads

Newsletter

Subscribe to our mailing list to get the new updates!