-

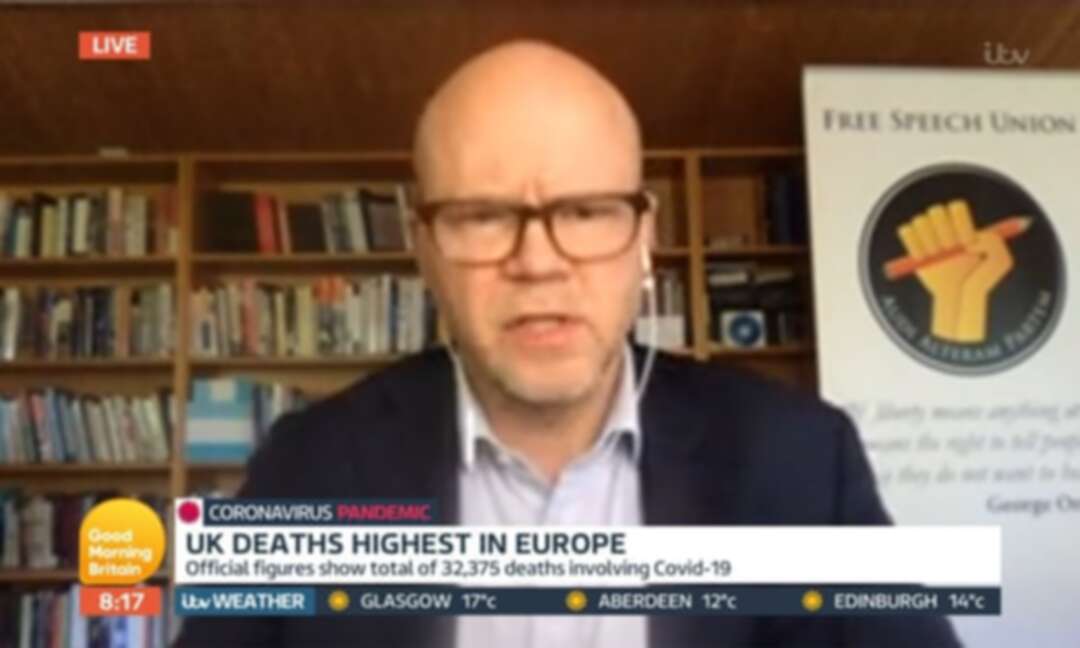

Students quit free speech campaign over role of Toby Young-founded group

Recruits say they were misled about the involvement of controversial pressure group the Free Speech Union

When a group of student activists were recruited to create a freedom of expression campaign, they were optimistic that their wide-ranging views could be part of its mission “to get all young people enthusiastic about free speech”.

The reality of the Free Speech Youth Advisory Board, they say, was rather different.

Instead of finding a forum for their hopes of opposing repressive regimes and helping minority voices to get heard, they claim that they were censured if they disagreed with the group’s right-of-centre orthodoxy. And they say they were dismayed to realise that the supposedly grassroots project appeared to be an “astroturfed” front for Toby Young’s controversial pressure group, the Free Speech Union (FSU).

“We have been used by Toby Young to legitimise this project,” said Harry Walker, president of the Bristol Free Speech Society, who emphasised that he spoke in a personal capacity. “Organisations like the FSU are just perpetuating a culture war.”

Maya Thomas, an Oxford University student and founder of the Oxford Society for Free Discourse, claimed: “They said very clearly this is a grassroots movement. They purposely hushed the FSU’s involvement down.”

Days ahead of a planned launch of the Free Speech Champions arm of the FSU, the Guardian has learned that at least six of the founding 16 participants have withdrawn from the campaign.

An email to organisers claimed that “this project seems to have been in the works for months, originating effectively as an FSU youth wing rather than the ‘independent grassroots movement’ it was pitched to us as”.

Inaya Folarin Iman, a director of FSU who led work on the project, told the Guardian: “This is my initiative, but I am a founding member of the board of the Free Speech Union and I have always been very open about the FSU’s involvement and sponsorship … No doubt the students who have contacted you see themselves as supporting free speech, but the Free Speech Champions project is unequivocal that it is an indivisible right and a fundamental civic virtue.” Young did not respond to a request for comment.

The resignations, which highlight a seething debate over the definition of free speech on campuses, may come as a blow to Young’s plans to influence university “cancel culture” debates through the FSU. Since he founded the group in February last year, it has largely intervened in cases of interest to the libertarian right, embroiling itself in identity politics, anti-trans activism and “lockdown scepticism”.

Despite those apparent focuses, Young – whose supporters include the historian David Starkey and the journalists Allison Pearson and Julia Hartley-Brewer – insisted last year that he wanted the FSU to appeal across the political and demographic spectrum, saying the organisation “isn’t just for male, pale and stale conservatives like me”.

More than 80% of the 85 directors, staff and advisers listed on the FSU website are male and more than 90% of those whose ethnicity could be determined are white.

Walker and Thomas were both approached to join the group. They and a recent Portsmouth graduate, Charlotte Nürnberg, told the Guardian that they found the promise of an open forum to be empty. “The group started with quite diverse viewpoints,” said Nürnberg, an activist and committee member of her university debating society until she graduated. “But very quickly that got shut down.”

In two emails to organisers explaining their departure, the trio, along with another member of Bristol’s Free Speech Society, Ben Sewell, claimed that the reality of the FSU’s involvement had been deliberately withheld when they signed up.

“We were led to believe that

A subsequent email to Iman confirming their departure added: “some of us even asked specifically about FSU involvement … and were told that it was negligible.”

Emails and social media messages seen by the Guardian suggest that during the recruitment process – which sought branding help with “name ideas, edgy marketing tactics, things which you’d find cool” – students were led to believe that a separate group led by Iman, the Equiano Project, was behind the plans.

An online application form and introductory email both mention the Equiano Project but not the FSU. Jan Macvarish, a sociologist and education director at the FSU who was present at the first meeting, was introduced as an observer but swiftly took on a major role in shaping the discussion, they said. Macvarish did not respond to a request for comment.

“Jan and Inaya dictated the ideological dogma of the group,” one of the students who left the group said. “‘This is correct free speech, this is wishy-washy free speech.’”

While some on the left of the group sought to make the case that it should seek to win support by emphasising the universality of free speech and raising concerns about repressive regimes silencing protest, Macvarish told them in a WhatsApp chat: “The degree to which citizens of China or Hungary have fs

Instead, WhatsApp discussions were largely dominated by discussions of such figures as the self-styled “professor against political correctness” Jordan Peterson and anti-trans activists.

As time went on, the role of the FSU became more explicit, the disaffected group say, with Young himself appearing at one of the Zoom sessions. They claim that those who disagreed with the FSU’s worldview were portrayed as not committed to free speech.

After Walker said in one discussion that he would “punch a Nazi”, saw Peterson as a peddler of “bought speech” and felt that marginalised groups were often denied true freedom of speech, Iman emailed him about “a few things that you mentioned on the call that I wanted to pick up with you for clarification”.

She added: “A level of synthesis is important for the project to demonstrate coherence … I aim for this free speech project to move away from an identity politics-based framework.” Walker said he viewed those comments as “a way of implying” that he was not welcome to express his views.

The controversy caps an awkward week for the FSU and its supporters which began with Pearson, a Daily Telegraph columnist and member of the group’s Media/PR advisory council, appearing to contradict its opposition to “cancel culture” by threatening to sue someone who she said had defamed her on Twitter, warning that she would contact his boss, and adding: “You’re finished”. She subsequently accepted an apology.

On Wednesday, Young was asked on Newsnight why he had written in June that “the virus has all but disappeared” and said “hands up, I got that wrong” before continuing his argument against lockdowns.

https://twitter.com/BBCNewsnight/status/1346605895300640768

With the dangers of the “wokerati” often in the news, Young and the FSU – which costs between £25 and £250 a year for membership – have frequently found themselves on the frontline of a culture war and celebrating victories wherever they can find them.

After a judge dismissed the group’s attempt to win a judicial review of Ofcom’s role in regulating misinformation about coronavirus and called it “not properly arguable”, “premised on a misinterpretation”, and “untenable”, the FSU Twitter account posted: “Thanks to us, @ofcom has stopped censoring Covid dissidents. The price of freedom is eternal vigilance.” In fact, the price of the case was the £16,732 the FSU was ordered to pay to cover Ofcom’s costs.

source: Archie Bland

Levant

You May Also Like

Popular Posts

Caricature

BENEFIT Sponsors BuildHer...

- April 23, 2025

BENEFIT, the Kingdom’s innovator and leading company in Fintech and electronic financial transactions service, has sponsored the BuildHer CityHack 2025 Hackathon, a two-day event spearheaded by the College of Engineering and Technology at the Royal University for Women (RUW).

Aimed at secondary school students, the event brought together a distinguished group of academic professionals and technology experts to mentor and inspire young participants.

More than 100 high school students from across the Kingdom of Bahrain took part in the hackathon, which featured an intensive programme of training workshops and hands-on sessions. These activities were tailored to enhance participants’ critical thinking, collaborative problem-solving, and team-building capabilities, while also encouraging the development of practical and sustainable solutions to contemporary challenges using modern technological tools.

BENEFIT’s Chief Executive Mr. Abdulwahed AlJanahi, commented: “Our support for this educational hackathon reflects our long-term strategic vision to nurture the talents of emerging national youth and empower the next generation of accomplished female leaders in technology. By fostering creativity and innovation, we aim to contribute meaningfully to Bahrain’s comprehensive development goals and align with the aspirations outlined in the Kingdom’s Vision 2030—an ambition in which BENEFIT plays a central role.”

Professor Riyadh Yousif Hamzah, President of the Royal University for Women, commented: “This initiative reflects our commitment to advancing women in STEM fields. We're cultivating a generation of creative, solution-driven female leaders who will drive national development. Our partnership with BENEFIT exemplifies the powerful synergy between academia and private sector in supporting educational innovation.”

Hanan Abdulla Hasan, Senior Manager, PR & Communication at BENEFIT, said: “We are honoured to collaborate with RUW in supporting this remarkable technology-focused event. It highlights our commitment to social responsibility, and our ongoing efforts to enhance the digital and innovation capabilities of young Bahraini women and foster their ability to harness technological tools in the service of a smarter, more sustainable future.”

For his part, Dr. Humam ElAgha, Acting Dean of the College of Engineering and Technology at the University, said: “BuildHer CityHack 2025 embodies our hands-on approach to education. By tackling real-world problems through creative thinking and sustainable solutions, we're preparing women to thrive in the knowledge economy – a cornerstone of the University's vision.”

opinion

Report

ads

Newsletter

Subscribe to our mailing list to get the new updates!