-

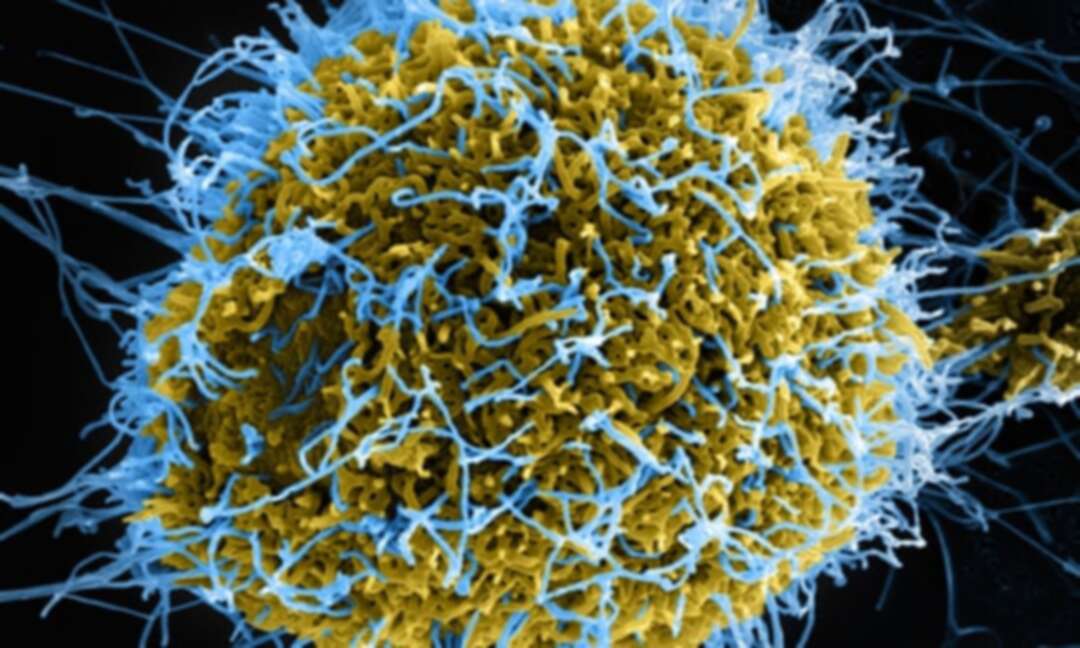

Scientists liken long Covid symptoms to those of Ebola survivors

Linda Geddes Experts also studying similarities with lasting effects of Chikungunya virus in hope of finding new treatments

Scientists are studying the similarities between long Covid and ongoing symptoms experienced by survivors of Ebola and Chikungunya virus in the hope of devising new treatments to improve their health.

Like patients with long Covid, survivors of these other, relatively new human viruses, often experience lingering symptoms which can make it difficult to work or function in everyday life.

For Ebola, roughly three-quarters of survivors are still experiencing symptoms a year after the initial infection, and sometimes for much longer – including joint and muscle pain, migraine-like headaches, visual problems and fatigue.

It’s a similar story for Chikungunya, a mosquito-transmitted virus that mostly affects people in African and Asian countries, causing fever and debilitating joint pain. Around a third of people go on to develop crippling arthritis that can last years, or other symptoms such as fatigue.

“It’s the same kind of discussions as we’re having for Covid; it’s people whose lives have never been the same again, who describe joint pain and fatigue and cognitive problems and all those familiar lists,” said Danny Altmann, a professor of immunology at Imperial College London.

“The experience of Chikungunya and Ebola should be sounding alarm bells, because although we’re talking about very different virus families, and very diverse infections, they seem to do quite similar things. There’s a desperate need for some immunology to understand what’s going on,” he said.

Some of those studies are starting to happen. Yves Lévy at Paris-Est Créteil University and colleagues have been analysing the blood of Ebola survivors in Guinea, two years after they were infected with the virus, which causes a severe and often fatal haemorrhagic fever.

Lévy said: “Usually, when you are fighting an infection there is inflammation and activation of the immune system, but this returns to a steady state once you recover. What we’re showing with Ebola is that the patients are recovering and the virus is gone, but they still have this persistent inflammation and immune activation.”

Whether this is the cause of their lasting symptoms is unclear, but other studies have shown a link between some of the inflammatory markers they identified and fatigue, said Miles Carroll, head of research at Public Health England’s national infection service, who is also studying Ebola survivors. “Just understanding that there is this link between prior infection and a chronic syndrome is a good start,” he added.

The cause of this inflammation is unclear. One possibility, is that small reservoirs of virus are surviving in places like the testicles or the eyeball, which immune system has less access to, but which nevertheless triggers a baseline level of immune activation. Another is that the virus is gone, but some of its proteins remain attached to the survivors’ cells, so the immune system attacks these instead. Or, that it just takes the immune system a long time to recover after Ebola. “We need to follow these patients in the long term, because, when they say they have symptoms, it is clearly not just a psychological issue,” Lévy said.

His team is currently performing the same analysis on the blood of patients who have recovered from Covid-19: “It’s not impossible that these Covid patients retain some inflammatory markers in the long term, as we see in Ebola.”

Similar studies are being done in people who’ve recovered from Chikungunya virus, including by Lisa Ng, senior principal investigator at the Singapore Immunology Network. She stresses that Chikungunya is very different to Covid-19; although debilitating, it rarely causes severe disease or respiratory syndromes. However, “some parallels could be fatigue, weakness and sense of tiredness, like many post-viral outcomes. These could be due to the lingering effects of the virus as the body continues to clear it out. It is like a tug-of-war between the patient and the virus.”

Although the exact mechanisms underpinning these lingering symptoms have yet to be fully defined, one clue comes from T helper cells – a set of immune cells which play a major role in instigating and shaping the immune response to viruses. Ng’s studies suggest they may be contributing to ongoing inflammation in the joints of people who’ve recovered from Chikungunya.

Such insights could lead to potential treatments, such as the repurposing of existing anti-inflammatory drugs, or the development of new immunotherapies for such post-viral syndromes.

Whether similar immune responses underpin long Covid is still unclear, but there is already some evidence that “friendly fire” from the immune system may be implicated in some cases.

But if there’s another lesson to be learned from Chikungunya, it is that these patients with lasting symptoms can’t simply be ignored. “Chikungunya is destroying the Brazilian health service, and it’s not so much because of the acute infection, but because of these lasting health problems,” said Altmann.

“I’m not sure our policymakers have this on board when they think about long Covid – that we may not just be talking about getting through this winter or this spring, but perhaps 300,000 people in the UK and rising, who have a chronic problem.”

source: Linda Geddes

Levant

You May Also Like

Popular Posts

Caricature

BENEFIT Sponsors BuildHer...

- April 23, 2025

BENEFIT, the Kingdom’s innovator and leading company in Fintech and electronic financial transactions service, has sponsored the BuildHer CityHack 2025 Hackathon, a two-day event spearheaded by the College of Engineering and Technology at the Royal University for Women (RUW).

Aimed at secondary school students, the event brought together a distinguished group of academic professionals and technology experts to mentor and inspire young participants.

More than 100 high school students from across the Kingdom of Bahrain took part in the hackathon, which featured an intensive programme of training workshops and hands-on sessions. These activities were tailored to enhance participants’ critical thinking, collaborative problem-solving, and team-building capabilities, while also encouraging the development of practical and sustainable solutions to contemporary challenges using modern technological tools.

BENEFIT’s Chief Executive Mr. Abdulwahed AlJanahi, commented: “Our support for this educational hackathon reflects our long-term strategic vision to nurture the talents of emerging national youth and empower the next generation of accomplished female leaders in technology. By fostering creativity and innovation, we aim to contribute meaningfully to Bahrain’s comprehensive development goals and align with the aspirations outlined in the Kingdom’s Vision 2030—an ambition in which BENEFIT plays a central role.”

Professor Riyadh Yousif Hamzah, President of the Royal University for Women, commented: “This initiative reflects our commitment to advancing women in STEM fields. We're cultivating a generation of creative, solution-driven female leaders who will drive national development. Our partnership with BENEFIT exemplifies the powerful synergy between academia and private sector in supporting educational innovation.”

Hanan Abdulla Hasan, Senior Manager, PR & Communication at BENEFIT, said: “We are honoured to collaborate with RUW in supporting this remarkable technology-focused event. It highlights our commitment to social responsibility, and our ongoing efforts to enhance the digital and innovation capabilities of young Bahraini women and foster their ability to harness technological tools in the service of a smarter, more sustainable future.”

For his part, Dr. Humam ElAgha, Acting Dean of the College of Engineering and Technology at the University, said: “BuildHer CityHack 2025 embodies our hands-on approach to education. By tackling real-world problems through creative thinking and sustainable solutions, we're preparing women to thrive in the knowledge economy – a cornerstone of the University's vision.”

opinion

Report

ads

Newsletter

Subscribe to our mailing list to get the new updates!