-

Lebanon’s political deadlock has no easy solutions: Experts

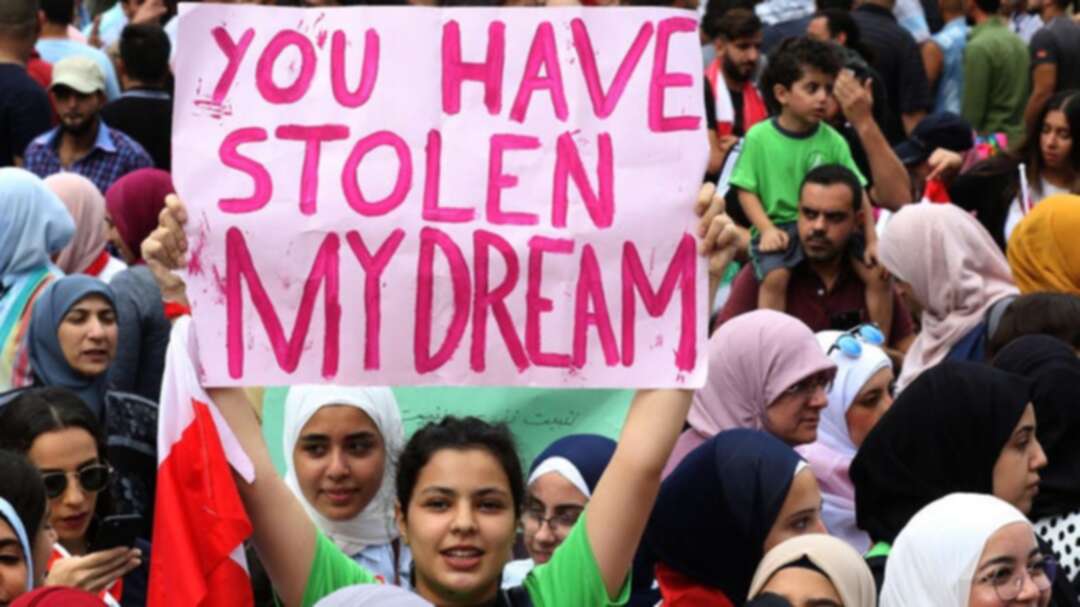

Since nationwide protests prompted the resignation of former Prime Minister Saad Hariri, Lebanon has been in a political deadlock. With no prime minister or cabinet amid a looming economic collapse, something must change in Lebanese politics – but it is unclear what.

No obvious alternatives to Hariri for PM

The immediate challenge is to find a replacement prime minister for Hariri.

Mohammad Safadi, who was endorsed by all the major political parties as a candidate to replace Hariri, withdrew after protesters took to the streets to denounce him.

“Protesters are asking for a government constituted and lead by independent, competent and non-corrupt figures. Mohammad Safadi does not comply with any of the above,” explained Hala Bejjani, Managing Director at the Lebanese human rights organization Kulluna Irada.

But choosing a new figure who meets protesters’ demands and is acceptable to the ruling elite is no easy task. No clear leader has emerged from the protests. Even if one did, the ruling political parties are likely to be hostile to any figure who challenges their interests.

Any new prime minister must “obtain the trust of the protesters, be representative of the ‘Sunni’ community

The deadlock has led some protesters in Sunni-majority Tripoli to begin mulling the return of Hariri despite protesting the status quo, revealed a report by Al Arabiya English.

Hariri himself is reportedly open to the idea and is seemingly deeply involved in the process of choosing the next prime minister – whether himself or someone else. On Wednesday, the Deputy Parliament Speaker Elie Ferzli was reported as saying “the will of Hariri” would determine the next prime minister, making it unlikely that the candidate chosen would represent a significant challenge to the current political status quo.

But the deadlock over the next prime minister is just one part of broader debates and uncertainty surrounding the future government in Lebanon.

Technocrats – but who?

Both anti-government protesters and government ministers from all the major parties have called for governance by “technocrats” or “specialists” as a potential solution to the current crisis.

Hariri has reportedly made his return as prime minister conditional on a cabinet of “independent technocratic ministers,” which would result in ousting his political rivals in government from the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), Hezbollah, and Amal. These parties are open to the idea of Hariri as prime minister but want a “techno-political cabinet,” which Bejjani said, “is meant to keep some of the ministries in the hand of the traditional forces, and specifically the defense and interior ministries.”

Meanwhile, anti-government protesters, many of whom are committed to the entire resignation of the cabinet, have also pointed to a new technocratic cabinet as the solution.

But the term “technocrat” is “very vague,” points out Sami Zaghoub, Public Policy Researcher at the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, allowing for multiple interpretations. According to Bejjani, some protesters are instead deliberately advocating for “politically independent, competent specialists” to avoid negative connotations associated with technocrats.

“

Without an in-depth roadmap from demonstrators, it is unclear how a technocratic government would be able to solve Lebanon’s deeply entrenched political and economic problems. Protesters have been hostile to plans by Hariri or President Michel Aoun to use technocrats to push through their legislative agendas, which have been dismissed as insufficient to solve Lebanon’s deep-seated problems.

But any new Cabinet would require a new prime minister and the political support of enough of the elite to be functional. Without being elected, a technocratic government risks being appointed by the very political elite which protesters view as corrupt and partisan.

Even if elections were called, Lebanon’s current electoral system benefits the established political parties, with elections based on confessional affiliation. Civil society lists likely to be favored by protesters have struggled to a breakthrough in the past, with Paula Yacoubian currently the only MP from an independent electoral list associated with civil society organizations.

Radical alternatives – and risks

Other protesters have called for a more radical overhaul of the entire system.

Lebanon’s confessional system, in which politicians are elected along sectarian lines, has long been called out by politicians and protesters across the political spectrum – including many who benefit from it.

These protests have amplified those demands, with a younger generation deliberately avoiding any party political or sectarian symbols and various denominations revolting against the parties which claim to represent them, including Hezbollah.

“Protestors are denouncing a failed economic politic based on the capture of all the state constituencies by a group of sectarian leaders that were the warlords of the war that ended in 1991,” said Bejjani.

But in a country with a violent history, challenging the status quo – set up with the Taif Accord, which was seen as ending the Lebanese Civil War – comes with significant risks.

“The capture of the state by the sectarian powers is so complete, that an alternative system altogether means a total collapse of the political, social and economic fabric of the country,” warned Bejjani.

In this context, the country’s delicate political and sectarian balance could unravel, with Israel, Syria, Iran and other regional countries all able to influence Lebanese politics.

The risk is heightened due to the country’s ongoing economic difficulties, with experts predicting a severe economic crash on the horizon. Shortages of medical supplies and food are already setting in as banks have imposed withdrawal limits and reduced credit lines.

Louis Hobeika, an Economics Professor at Notre Dame University in Lebanon, also told Al Arabiya English that he had concerns over the ability of the Lebanese economy to meet protesters’ demands.

“What people are expecting from the public sector is no way compared to what the public sector can provide, unfortunately,” he said.

And economic problems are likely to further fuel discontent. “With lay-offs, devaluation of the lira and a consequent drop in the power purchase of a large number of Lebanese, we might be soon witnessing social unrest,” warned Bejjani.

Despite these risks, Lebanese people across the country continue to turn out onto the streets to denounce the political establishment and sustain the revolution until all of their demands are met - even if it is unclear what those demands will bring about.

source: Tommy Hilton

You May Also Like

Popular Posts

Caricature

BENEFIT Sponsors BuildHer...

- April 23, 2025

BENEFIT, the Kingdom’s innovator and leading company in Fintech and electronic financial transactions service, has sponsored the BuildHer CityHack 2025 Hackathon, a two-day event spearheaded by the College of Engineering and Technology at the Royal University for Women (RUW).

Aimed at secondary school students, the event brought together a distinguished group of academic professionals and technology experts to mentor and inspire young participants.

More than 100 high school students from across the Kingdom of Bahrain took part in the hackathon, which featured an intensive programme of training workshops and hands-on sessions. These activities were tailored to enhance participants’ critical thinking, collaborative problem-solving, and team-building capabilities, while also encouraging the development of practical and sustainable solutions to contemporary challenges using modern technological tools.

BENEFIT’s Chief Executive Mr. Abdulwahed AlJanahi, commented: “Our support for this educational hackathon reflects our long-term strategic vision to nurture the talents of emerging national youth and empower the next generation of accomplished female leaders in technology. By fostering creativity and innovation, we aim to contribute meaningfully to Bahrain’s comprehensive development goals and align with the aspirations outlined in the Kingdom’s Vision 2030—an ambition in which BENEFIT plays a central role.”

Professor Riyadh Yousif Hamzah, President of the Royal University for Women, commented: “This initiative reflects our commitment to advancing women in STEM fields. We're cultivating a generation of creative, solution-driven female leaders who will drive national development. Our partnership with BENEFIT exemplifies the powerful synergy between academia and private sector in supporting educational innovation.”

Hanan Abdulla Hasan, Senior Manager, PR & Communication at BENEFIT, said: “We are honoured to collaborate with RUW in supporting this remarkable technology-focused event. It highlights our commitment to social responsibility, and our ongoing efforts to enhance the digital and innovation capabilities of young Bahraini women and foster their ability to harness technological tools in the service of a smarter, more sustainable future.”

For his part, Dr. Humam ElAgha, Acting Dean of the College of Engineering and Technology at the University, said: “BuildHer CityHack 2025 embodies our hands-on approach to education. By tackling real-world problems through creative thinking and sustainable solutions, we're preparing women to thrive in the knowledge economy – a cornerstone of the University's vision.”

opinion

Report

ads

Newsletter

Subscribe to our mailing list to get the new updates!