-

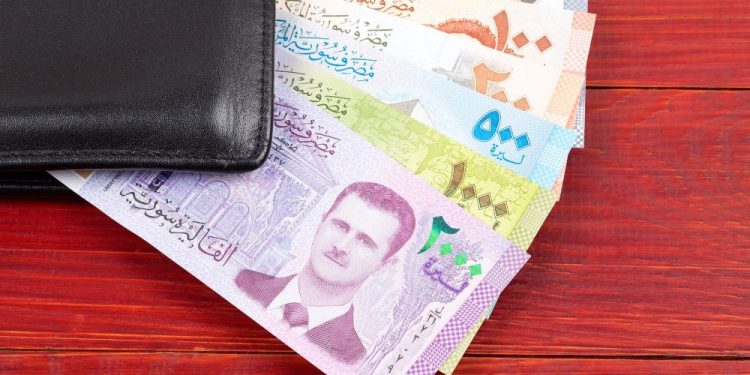

Syrian diaspora helps regime unwillingly with fees to avoid military conscription

The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project reported, large fees to avoid military conscription have helped turn Syria’s diaspora into a major source of revenue for the cash-strapped government. Men who don’t pay face the threat of their family’s assets in Syria being seized.

The report talks about Yousef, a 32-year-old Syrian living in Sweden, found himself faced with an impossible choice: Either enlist in the army of the government that made him a refugee, or risk his family losing their home back in Syria.

The report said, military service is mandatory for Syrian men between the ages of 18 and 42, and the stakes rose significantly in February when an army official announced on Facebook that a new regulation would allow authorities to confiscate the property of “service evaders” and their families. Pressure was mounting on Yousef to decide.

In June, Yousef made his way to the Syrian Embassy in Stockholm with $8,000 in cash, ready to pay the fee to have his name taken off the conscription rolls. A shiver ran down his spine as he collected his receipt.

Yousef told OCCRP, his voice trembling: “This money will be used by the Syrian regime to buy weapons and kill more people.”

Read more: A report from YASA and Ceasefire Centre shows the human rights situation in Afrin

Yousef's case is not the only case. About a fifth of Syria’s population of 17 million are men of military age, according to data from the World Bank. With some 6.6 million Syrians having fled abroad since the protest movement of early 2011 slipped into civil war, there are likely to be hundreds of thousands in Yousef’s position.

Studies have shown that the threat of being conscripted is a major reason many refugees fear returning to Syria.

According to the report, the Syrian government has been able to leverage this anxiety into revenue, harvesting foreign currency from the roughly 1 million Syrians who have settled in Europe to help prop up their ailing budget after U.S. sanctions cut them off from the international banking system last year.

Syrian embassies, which used to only process paperwork for the military exemptions, have recently begun collecting cash payments.

Two researchers, an airport official, and a former diplomat interviewed by OCCRP and the Syrian Investigative Reporting Unit (SIRAJ), said they suspected the cash makes its way back to Syria via diplomatic pouch.

Read more: Biden administration expected to renounce sanctions on Bashar al-Assad

The report said that although it is difficult to determine exactly how many Syrians have paid the military exemption fees, government documents and official statements show that Bashar Al-Assad’s government projected that the policy would raise substantial income.

The findings speak to the lengths the Syrian government is going to in order to raise cash, and raise questions about when exactly sovereign relations between a government and citizens slip into a form of extortion.

Syria’s army, finance ministry, foreign ministry, central bank, and military recruitment service did not respond to requests for comment. U.S. authorities declined to comment.

The Caesar Act implemented in June last year has worsened an already difficult financial situation for Syria, cutting off its access to the international banking system. Processing payments for vital imports such as wheat and oil products became even harder, and the Syrian pound — now worth barely one percent of its pre-crisis value against the dollar — suffered further losses.

Read more: Levant center for Strategic Studies holds conference on ‘The Political Islam and Europe’

“Shortage in foreign currency has become an acute problem, especially after the Caesar Act came into force," Armenak Tokmajyan, a researcher at the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut, told OCCRP. “The regime needs foreign currency. The more it has, the longer it will survive.”

Because of the increasing pressures, the Syrian government has leaned increasingly on its diaspora to fill its coffers. A Syrian passport is now one of the world’s most expensive to obtain abroad, at about £220 for a new passport, and about £600 to get it expedited.

The military exemption fees are even more substantial.

According to a parliamentary study from 2015 — the year after Syria raised the fee — predicted that payments to avoid service could bring in over $1.2 billion a year, even if only 10 to 15 percent of Syrians wanted for conscription actually paid up, Mujeeb Al-Rahman Al-Dandan, a Syrian member of parliament, told local radio in an interview in November last year.

Read more: EU says: Europe and China must continue engaging despite differences

The study has not been made public. But according to Dandan, it found that annual revenues from the fee could rise to between $2 to $3 billion within five years, meaning it would be a “good contributor to the treasury” and could even “help raise the wages of public servants, including military personnel.”

Syria’s 2021 budget projection predicts revenues from the military exemption fees to reach 240 billion Syrian pounds — about $190 million at the official exchange rate — up from 70 billion pounds in 2020, according to copies published in Syria’s Official Gazette.

Syrian economist Karam Shaar told OCCRP, the estimated revenue makes up 3.2 percent of this year’s budget revenue, up from 1.75 percent in 2020.

Sweden illustrates how the new amendments have played out among Syria’s diaspora. The Scandinavian country hosts about 114,000 of the roughly 1 million Syrian refugees in Europe and is home to tens of thousands of relatively new arrivals as well as second- and third-generation Syrians.

Between June and August, OCCRP reporters made three visits to the Syrian embassy in Stockholm. They counted an average of 10 applicants a day waiting in the queue for military service exemption.

Another hint of how many people were paying the exemption fees came a year earlier, in June 2020, when the embassy website published the names of 43 Syrians cleared to pay the fee. It is unclear exactly when those on the list applied, but for other procedures, such as passport issuance, the embassy usually issues its lists once per month.

Read more: What is the best policy in controlling the Iranian regime’s nuclear ambitions?

An embassy employee — speaking to an undercover OCCRP reporter who did not identify himself — said he could not say exactly how many had applied for the service exemption, but that there had been a "significant increase" in the first half of 2021, which he attributed to Bitar’s statement.

The employee said, “On some days, 10 come to us and on other days the figure can go up to 50.” According to the report, if accurate, this would mean the embassy could be taking in as much as $400,000 in cash on some days.

OCCRP spoke with ten Syrians — eight in Sweden, one in Germany, and one in Lebanon — who decided to pay the conscription fee. Some, like Yousef, were frightened by the prospect of asset seizures in Syria. Others had more practical reasons.

One 29-year-old named Ali said he paid the fee at the encouragement of his family, who considered the payment to be “a form of direct participation in the Syrian war effort”.

Read more: North Korea tests new hypersonic missile called Hwasong-8

Gian, a Syrian who works at a home for elderly people in Frankfurt, Germany, said he had no issue in paying the money. “I am getting a monthly salary, the exemption process is easy, and I want to safeguard my family’s property in Syria from being seized,” Gian said. He said three relatives with asylum status in Germany also paid the fee.

But many Syrians are still leery of funding the government they feel was responsible for sending them into exile.

Abdullah Jaafar, a 35-year-old who has been living in Gothenburg, Sweden’s second-largest city, for eight years, said he saw the exemption payments as a kind of extortion.

“I have the full amount, and I can pay it, but I will not do it,” Jaafar said. “This government is illegal.”

Source: OCCRP

You May Also Like

Popular Posts

Caricature

BENEFIT Sponsors BuildHer...

- April 23, 2025

BENEFIT, the Kingdom’s innovator and leading company in Fintech and electronic financial transactions service, has sponsored the BuildHer CityHack 2025 Hackathon, a two-day event spearheaded by the College of Engineering and Technology at the Royal University for Women (RUW).

Aimed at secondary school students, the event brought together a distinguished group of academic professionals and technology experts to mentor and inspire young participants.

More than 100 high school students from across the Kingdom of Bahrain took part in the hackathon, which featured an intensive programme of training workshops and hands-on sessions. These activities were tailored to enhance participants’ critical thinking, collaborative problem-solving, and team-building capabilities, while also encouraging the development of practical and sustainable solutions to contemporary challenges using modern technological tools.

BENEFIT’s Chief Executive Mr. Abdulwahed AlJanahi, commented: “Our support for this educational hackathon reflects our long-term strategic vision to nurture the talents of emerging national youth and empower the next generation of accomplished female leaders in technology. By fostering creativity and innovation, we aim to contribute meaningfully to Bahrain’s comprehensive development goals and align with the aspirations outlined in the Kingdom’s Vision 2030—an ambition in which BENEFIT plays a central role.”

Professor Riyadh Yousif Hamzah, President of the Royal University for Women, commented: “This initiative reflects our commitment to advancing women in STEM fields. We're cultivating a generation of creative, solution-driven female leaders who will drive national development. Our partnership with BENEFIT exemplifies the powerful synergy between academia and private sector in supporting educational innovation.”

Hanan Abdulla Hasan, Senior Manager, PR & Communication at BENEFIT, said: “We are honoured to collaborate with RUW in supporting this remarkable technology-focused event. It highlights our commitment to social responsibility, and our ongoing efforts to enhance the digital and innovation capabilities of young Bahraini women and foster their ability to harness technological tools in the service of a smarter, more sustainable future.”

For his part, Dr. Humam ElAgha, Acting Dean of the College of Engineering and Technology at the University, said: “BuildHer CityHack 2025 embodies our hands-on approach to education. By tackling real-world problems through creative thinking and sustainable solutions, we're preparing women to thrive in the knowledge economy – a cornerstone of the University's vision.”

opinion

Report

ads

Newsletter

Subscribe to our mailing list to get the new updates!