-

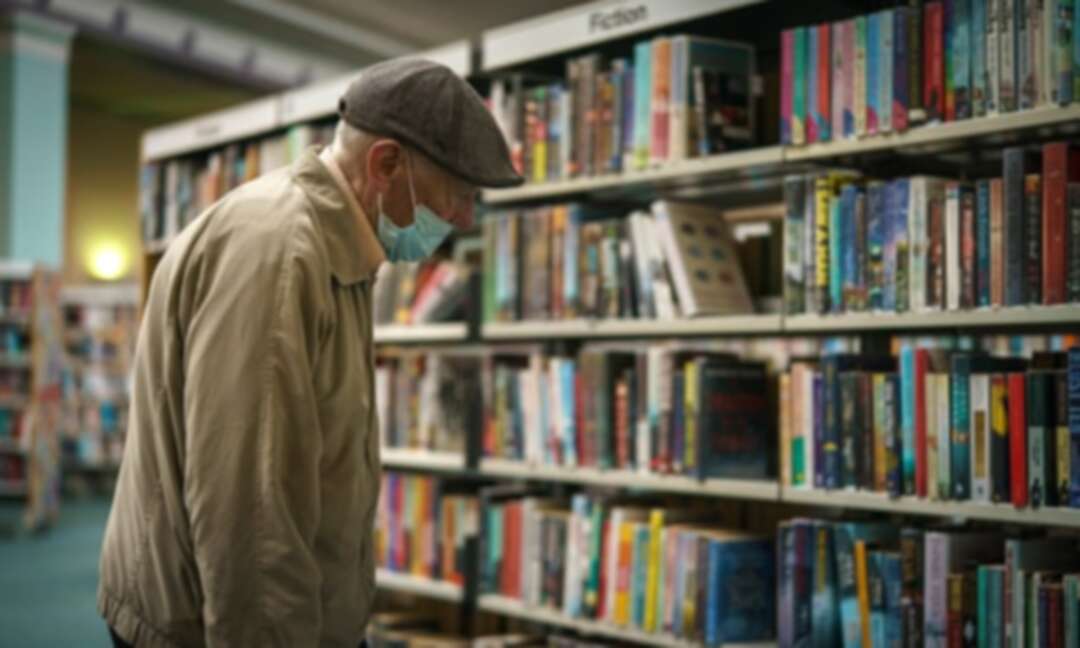

Covid has exposed dire position of England's local councils

The pandemic has wrecked finances as well as revealing deeper roots of a funding crisis in local government

The pandemic has a habit of bringing hidden social crises into the open. Now it reveals the precarious position of local government, the provider of vital services from care homes to public health and bin collection, which has helped keep the show on the road in the UK’s biggest national emergency since the second world war.

The National Audit Office (NAO) account of the near implosion of England’s local councils during Covid is sobering: only by the government’s swift, if grudging, injection of billions of pounds of emergency cash into council coffers over recent months did ministers avert what the auditors call “system-wide financial failure”.

The watchdog rightly praises ministers for this: the consequences of scores of local authorities having to declare bankruptcy in the middle of lockdown are frightening. But it makes two other points: first, that 10 years of austerity made municipal finances structurally fragile; and second, that councils’ budget crisis isn’t over.

It makes clear successive Tory governments not only dismantled the town hall roof but failed to fix it by the time hurricane Covid blew in. Council spending was cut by a third, rising demand for social care was ignored and council budgets made reliant on the whims of local income, whether council tax or car parking charges.

Grand, longstanding government plans to reform local government and social care funding failed to materialise. For years, councils patched up their threadbare budgets by using up financial reserves and cutting frontline services. The more ambitious borrowed billions to spend on risky office and retail investments.

So when Covid arrived, council spending rocketed, income crashed and many found they had little in the way of rainy-day cash reserves. As the NAO puts it: “Funding reductions … means that authorities’ finances were potentially more vulnerable to the impact of the pandemic that they would have been otherwise.”

Only one council – Croydon – went bust this financial year. Yet at least seven more have had or asked for government bailouts to head off insolvency. When the NAO surveyed councils in December, it assessed that 25 were at acute or high risk of financial failure, and a further 92 at medium risk of insolvency.One bailout loan recipient, Luton, was reliant on a £33m-a-year dividend from its ownership of Luton airport to pay for its core services. When Covid brought air travel to an abrupt halt, so the council’s finances collapsed. In July it pushed through £17m of service cuts to stay afloat. Even that, it seems, was not quite enough.

The government has encouraged councils to quietly come to it for help, rather than unilaterally declare insolvency. Wary perhaps of the alarming optics of a long line of council leaders queueing up for rescue funds, it refuses to say how many councils have approached it for emergency bailouts.

The NAO makes it clear the future is uncertain. Many councils have little confidence in the robustness of the 2021-22 budgets they have just voted through. Most expect to make more cuts – not least because the government has failed to fully compensate them for Covid spending – and to endure more years of financial uncertainty.

The NAO urges the government to draw up a long-term plan for councils to help them recover from the “financial scarring” caused by the pandemic. Until it does so, local authorities – and the services they provide – face more years of uncertainty and agonising cuts decisions.

source: Patrick Butler

Levant

You May Also Like

Popular Posts

Caricature

BENEFIT Sponsors BuildHer...

- April 23, 2025

BENEFIT, the Kingdom’s innovator and leading company in Fintech and electronic financial transactions service, has sponsored the BuildHer CityHack 2025 Hackathon, a two-day event spearheaded by the College of Engineering and Technology at the Royal University for Women (RUW).

Aimed at secondary school students, the event brought together a distinguished group of academic professionals and technology experts to mentor and inspire young participants.

More than 100 high school students from across the Kingdom of Bahrain took part in the hackathon, which featured an intensive programme of training workshops and hands-on sessions. These activities were tailored to enhance participants’ critical thinking, collaborative problem-solving, and team-building capabilities, while also encouraging the development of practical and sustainable solutions to contemporary challenges using modern technological tools.

BENEFIT’s Chief Executive Mr. Abdulwahed AlJanahi, commented: “Our support for this educational hackathon reflects our long-term strategic vision to nurture the talents of emerging national youth and empower the next generation of accomplished female leaders in technology. By fostering creativity and innovation, we aim to contribute meaningfully to Bahrain’s comprehensive development goals and align with the aspirations outlined in the Kingdom’s Vision 2030—an ambition in which BENEFIT plays a central role.”

Professor Riyadh Yousif Hamzah, President of the Royal University for Women, commented: “This initiative reflects our commitment to advancing women in STEM fields. We're cultivating a generation of creative, solution-driven female leaders who will drive national development. Our partnership with BENEFIT exemplifies the powerful synergy between academia and private sector in supporting educational innovation.”

Hanan Abdulla Hasan, Senior Manager, PR & Communication at BENEFIT, said: “We are honoured to collaborate with RUW in supporting this remarkable technology-focused event. It highlights our commitment to social responsibility, and our ongoing efforts to enhance the digital and innovation capabilities of young Bahraini women and foster their ability to harness technological tools in the service of a smarter, more sustainable future.”

For his part, Dr. Humam ElAgha, Acting Dean of the College of Engineering and Technology at the University, said: “BuildHer CityHack 2025 embodies our hands-on approach to education. By tackling real-world problems through creative thinking and sustainable solutions, we're preparing women to thrive in the knowledge economy – a cornerstone of the University's vision.”

opinion

Report

ads

Newsletter

Subscribe to our mailing list to get the new updates!