-

Syria’s tragedy shames the world

In Washington on 5 February, Ambassador James Jeffrey, the US envoy for Syria engagement and special envoy to the global coalition to defeat ISIS, gave an on-the-record media briefing about the current situation. Jeffrey spoke unusually frankly. The US, he said clearly, is no longer demanding the downfall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, only that it reform and become less abusive.

“We’re not asking for regime change per se, we’re not asking for the Russians to leave, we’re asking for what the international community and the UN… has called for, for Syria to behave as a normal, decent country that doesn’t force half its population to flee, doesn’t use chemical weapons dozens of times against its own civilians, doesn’t drop barrel bombs, doesn’t create a refugee crisis that almost toppled governments in Europe, does not allow terrorists such as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham and particularly Daesh/ISIS to emerge and flourish in much of Syria.”

Jeffrey also talked about US pressure on Russia to modify its behaviour towards Assad, but that only served to emphasise how little direct influence the Trump administration has with both Damascus and Moscow, nearly nine years into the most destructive conflict in the Middle East.

The immediate context is the escalating humanitarian crisis in the north-western province of Idlib. Idlib was recently described succinctly by a BBC correspondent as a place where “the dead have no peace and the living are running out of space to breathe.” Hospitals, schools and bakeries have been damaged and destroyed. Ordinary people are desperate for food, clean water and medical care. Children are dying of exposure in freezing winter temperatures.

The UN, struggling to cope, is worried about refugee flows. New camps are being built near the Turkish border following the displacement of 800,000 civilians in the last two months. More land and resources are needed while airstrikes and shelling continue to devastate towns and villages.

Idlib, home to 3 million people, is the only part of Syria that is still outside Assad’s control. It was supposed to be protected by a de-escalation agreement brokered in 2018 by Russia and Turkey. But in recent weeks the area has been battered by an intensifying regime assault.

The deaths of several Turkish soldiers is nothing compared to what is likely to happen next. And the US is unlikely to intervene. The risk of a wider Turkish-Syrian confrontation, or even a Turkish-Russian one, is now rising alarmingly. On 14 February European members of the UN security council called for an immediate end to the Idlib offensive.

David Miliband, the former British foreign secretary and now head of the International Rescue Committee, has described the looming catastrophe as an outcome of the failure of diplomacy and the international community’s abandonment of Syrian civilians.

Looking back critically at the inconsistency of US and other policies is necessary to understand this grim story so far. Last week, near Qamishli in the northeast, there was a rare clash between US and Syrian forces, underlining the fact that ever since Trump suddenly severed the anti-ISIS pact with the Kurds last October – green-lighting a Turkish offensive - what remains of the US presence in Syria has faced mounting difficulties.

Still, not everything can be blamed on the unpredictable and disruptive Twitterer-in-chief in the Oval Office. Barack Obama famously called for Assad to go in 2011 – setting the tone for US allies – but then fatefully failed to observe his own “red line” when the regime, supported then as now by Moscow and Tehran, used chemical weapons to kill 1400 people in Eastern Ghouta in August 2013.

Samantha Power, Obama’s UN ambassador, described what she hoped would happen then: “Diplomacy had been ineffective in part because Assad had become convinced that no-one would stop him from using even the most merciless tactics against his own people,” she wrote in her memoir. “If the US government looked away from this incident, signaling that Assad could gas his citizens at will, I worried he would never feel sufficient pressure to negotiate.” Power’s fears were spot-on. Russia’s direct military intervention two years later radically altered the parameters of the war.

Fast-forwarding to the present, nobody now expects Assad to be overthrown. The best that can be hoped for is some sort of peaceful transition in Damascus. And the optimal way to achieve that, it is now argued, is for the US to actively support Turkey’s intervention – raising the stakes for both Vladimir Putin and Assad himself and conditioning post-conflict reconstruction aid on his departure.

Next month Syria’s war will enter its 10th year. Half a million people have died and nearly 15 million have been displaced at home and abroad. It is hard to be optimistic about the country’s future. But Waad al-Kataeb, who made the acclaimed film ForSama about Aleppo, transmitted a defiant but sad message, in beautiful Arabic script, on the dress she wore for the recent Oscar ceremony: “We dared to dream, and we don’t regret demanding our dignity.”

You May Also Like

Popular Posts

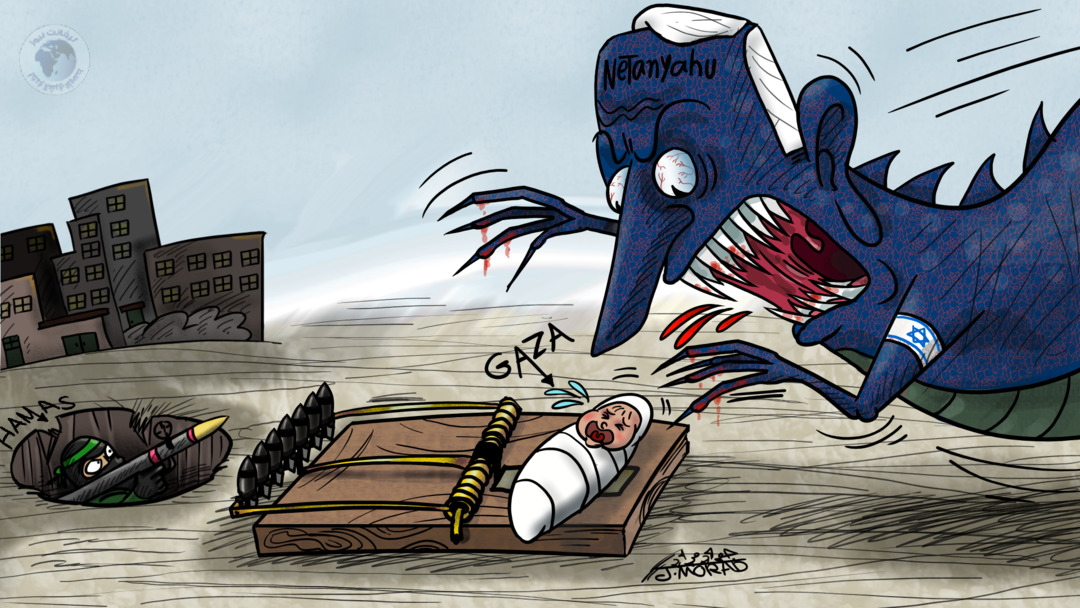

Caricature

opinion

Report

ads

Newsletter

Subscribe to our mailing list to get the new updates!